Sessions and the Flash

A single web server may, at any given time, be engaged in separate “conversations” with many different users. By conversation, we mean that a given user on a given browser is interacting with a website being served up by the server. The interaction produces a series of related HTTP request/response cycles between the browser and server. For example, Figure 1 illustrates a conversation between a user, Alice, who is navigating a website, and a web server that is serving up the web pages, images, etc.

Although conversations like this seem pretty intuitive to a human, they create a problem for servers. At its core, the HTTP protocol is stateless, providing no specific support for keeping track of which requests go with which conversations. Thus, each time an HTTP request the comes in, the server is not necessarily aware that this request is part of an ongoing conversation. This situation causes problems—for example, should a user have to re-authenticate every time their browser sends an HTTP request? That would get very annoying very quickly.

1. Sessions

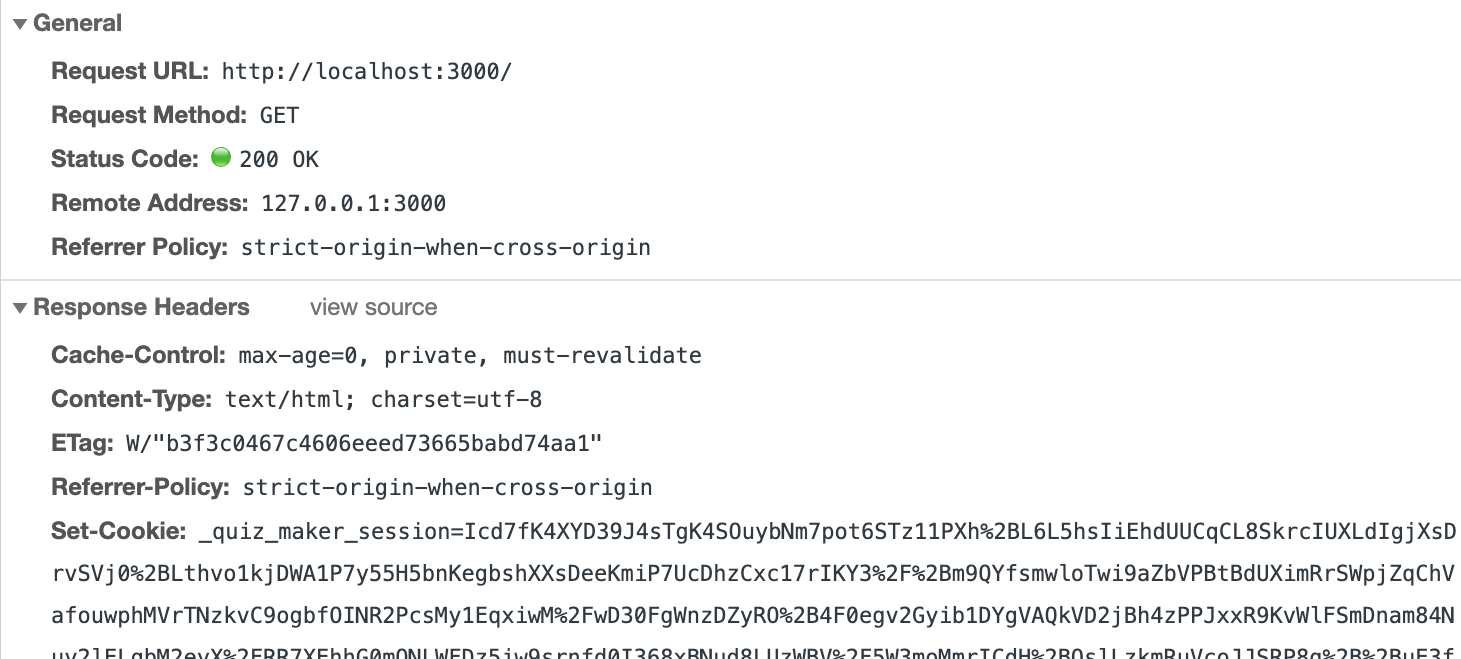

Servers commonly use sessions to store conversational state (i.e., data specific to a particular conversation). That is, the server reserves some memory for each conversation that is currently active. The server keeps track of which session goes with which browser using cookies. In short, cookies are some data that ride along in HTTP requests and responses passed between browsers and servers. To enable sessions, a conversing server and browser include in all their HTTP messages a cookie that contains a unique session ID. Figure 2 illustrates an HTTP request that includes a session cookie (see the “Set-Cookie: ...” bit). When the server receives an HTTP request with a session cookie, it can use the session ID to look up the session data it saved for that particular conversation.

In Rails, controller methods can store and retrieve session data using an instance method session (which behaves like a hash when you use it). For example, here is a line of controller code that would save the ID of the current user in the session under the key :current_use_id.

session[:current_user_id] = user.id

In subsequent requests, a controller method could use the session to look up the current user, like this:

current_user = User.find(session[:current_user_id])

In practice, I don’t write code that directly uses the session very often. However, authentication Gems, like Devise, make use of it under the hood, for example, to store the identity of the currently authenticated user.

2. The Flash

The flash is a special part of the session that helps solve a key problem in the development of web apps. To understand the problem, consider Figure 3. The figure depicts the HTTP requests and responses that typically result from a user opening a web form page and submitting data via the form. In particular, this interaction involves three requests and responses. The first request is to load the page containing the form. The second request happens when the user has entered data into the form and pressed submit. The response to the second request requires a little explanation.

It is a best practice in the design of web apps to respond to state-affecting operations (like POST, PATCH, and DELETE requests) with an HTTP redirect, instead of the HTML for a page. The rationale for this design decision stems from the reload button common to all web browsers. The way the reload button works is that, when pressed, the browser re-sends the last HTTP request it sent to the server. Thus, if the response to a POST request was an HTML page, and the user then reloaded that page, the browser would resubmit the form data, which is probably not what the user intended and could potentially result in erroneous duplicate data being stored in the database. Responding to POST requests with an HTTP redirect solves this problem, because the redirect causes the browser to send another HTTP GET request to retrieve a page specified by the redirect (the third request in Figure 3). Thus, if the user hit the reload button in this case, the browser would simply re-send the GET request for the redirected page, and it would not cause a resubmission of the form data.

The problem that the flash solves is that it is common to display a notification after a form is submitted (e.g., to indicate that the submission succeeded or failed). However, a controller action would process the form data during the second request/response cycle, but the notification would need to be rendered by a different controller action responding to the third request. So how does the third controller action know to render a notification that was the result of the second controller action?

The flash is a special kind of session storage designed to solve this problem. In particular, a notification message can be stored in the flash under a particular key. For example, a controller action might store an alert message in the flash, like this:

flash[:alert] = "Error: Unable to save data"

What makes the flash special is that this message will only be available during the processing of the next request of the session. Thus, it’s common to have code similar to this for displaying flash messages near the top of the body element of the application.html.erb file:

<% if flash[:alert] %>

<div class="alert"><%= flash[:alert] %></div>

<% end %>

Note that the if part of this HTML.ERB code makes it so that the view will render an alert-message div only if an alert message was set by the previous action of the session. If no alert message was set, then the div will not be rendered.

2.1. But What If You Need to Render the Flash Notification in the Same Request That Set It?

Although the above scenario is perhaps the most common in practice, it is sometimes the case that a controller action needs a notification to appear on a page that the controller action itself is rendering (and thus, the controller action does not want the notification to be rendered by the next controller action to run in the session). For example, Figure 4 depicts the HTTP requests that would result from this case. Note how they differ from the ones in Figure 3.

If the flash hash were used in the typical way for the example in Figure 4, there would be a problem: the flash notification would not appear in the second response (where we want it to). Instead, it would be available only to whatever request comes after the second one, but that’s not when we want it.

To solve this problem, there is a flash.now method that can be used to change the flash’s behavior. In particular, it causes the flash messages to be instantly available (and to be destroyed after the current request completes). Here is an example of how controller action code using flash.now might look:

flash.now[:alert] = "Error: Unable to save data"

Thus, if this controller action were to subsequently render an HTML page, the alert message would appear in that page.

3. Further Reading

For more info on sessions and the flash, see the Rails Guides: https://guides.rubyonrails.org/action_controller_overview.html#session